A few days ago, my husband, Tim, introduced me to a term I had missed somehow: “virtue signaling,” that is, letting others know via social media that you are more virtuous in your beliefs than they are regarding a certain social problem, without actually doing anything to address the problem.

Then Tim began to talk about his dad, who never did any purposeful “virtue signaling,” but was noticed simply because of his virtue in his interactions with others. In a turbulent time, he lived the kindness he taught, and it caused an uproar.

This is his story, a special for Father’s Day.

Guest post by my husband, Tim Davis

It’s time to come clean about my quiet and unassuming dad: he was a revolutionary. That’s not how I usually think of him or refer to him, and he would never have said it of himself. But he was.

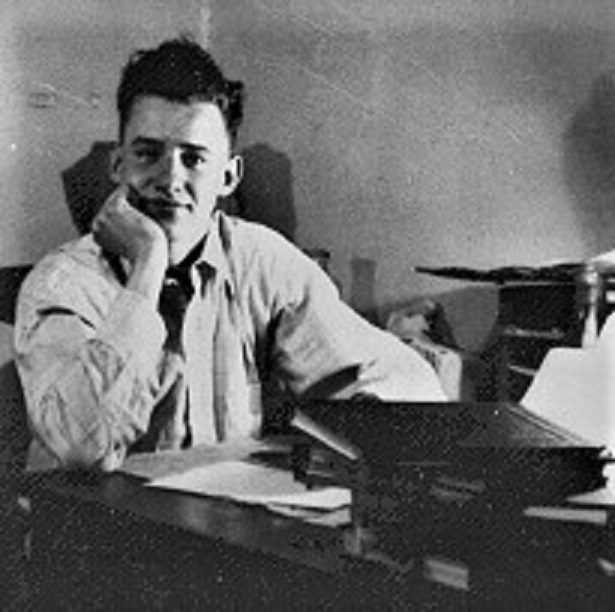

Tim’s dad as a student, before he became a pastor, unsuspecting that he would be a quiet revolutionary

His weapon of choice? Consistent kindness. And in 1965 that was often in short supply, especially when the issue was the color of a person’s skin.

By the time I was old enough to pester my two big sisters, our family lived in the mousey old parsonage on Main Street across from the church where my Dad, Everett R. Davis, pastored in a small town in western New York.

Those were the days when pastors were supposed to be poor, and the church made sure we were. Every year we waited for Dad’s Christmas bonus so we could go shopping for modest gifts at the last minute. Though life was stretched thin, still our lives seemed to be far removed from the chaotic, fast-changing world of the early sixties.

But in 1965 the Civil Rights Movement arrived in our little town. Our hundred-year-old church had barely ever had any black visitors, let alone members, but now that was being challenged. I remember one black woman came demanding she be admitted to membership. My dad responded that he’d be glad to talk with her about her faith. (She never came back.)

Then a whole black family visited, and I remember them as very gracious people. The McGills had five kids, a girl and four boys—two of them close to my age.

Of course, black kids my age were nothing new; my school had been integrated since my kindergarten year. But this family was coming over to our house, getting to know us well, parents praying together and laughing together, while we younger kids played outside with the teens joking around and keeping an eye on us.

Then the inevitable happened: the McGills wanted to join and become the first black members in the history of the church. Since they agreed with the statement of faith and lived lives of personal integrity, the pastor, my dad, welcomed them.

Our small community apparently believed this was a line that shouldn’t be crossed. I remember one well-to-do church couple inviting my parents to their home for a discussion, and as a child for whom no babysitter was available, I got a ringside seat.

The man spoke about the “curse on Canaan” and how it somehow meant that Negroes were not as advanced as whites. Even as a child I could barely believe someone would make such a claim, so I couldn’t really focus on my dad’s rebuttals from clear and relevant Scriptures. The discussion was calm, but we never saw that couple again. Others also left the church.

Maybe it was because of my mom’s family’s involvement with ministry to blacks in the U.S. and overseas, but to my child’s eyes it appeared that my parents didn’t blink when confronting racism around them. Treating all people as equals was not an adopted cause but was simply a natural outgrowth of who they were. More like business as usual.

But this was just the beginning.

When Dad was asked to officiate at the first black wedding in our church, he didn’t hesitate to say yes. Hazel McGill was married, with a handful of white guests mixed into the crowd, and another wave of murmuring washed through the church and community.

But the biggest resistance was yet to come. I remember as a child cheering for the school basketball team at the games with my big sisters and the crowd of their peers. One of the leading star basketball players? Willie McGill, the family’s oldest son. There was no doubt he was popular.

One summer Willie went to work at a Christian camp and later started dating one of the white girls he met there. Soon word came back around that this “problem” was at least partially my dad’s fault. By accepting blacks into membership in our church, Dad had set the stage for the forbidden practice known as “interracial dating.”

During this time, the McGill family came over more, and I had more time playing in the backyard with Dorsey and Robert. Though we generally had free rein through the whole neighborhood and nearby park, we felt the tension and sensed it would be better to stay in my own yard during those times. We knew some people in town were very angry and might not appreciate the sight of black boys in the neighborhood.

How it all played out? Was it a factor in our moving on from that town after my fourth grade year? Possibly.

Was it a factor in my Dad’s leaving the ministry for a while and accepting a teaching job at the New York State School for the Blind? Likely. As a child you often have only a vague sense of why your parents make the decisions they make.

And then as an adult you sometimes don’t have enough understanding or appreciation to ask them about it until after they’re gone.

But this I do know. Beginning in 1965, Dad was one of those people that changed history, just a little bit, in his own small sphere. In turbulent times, his influence spread by kindness and consistency. Dad rarely got involved in politics or even adopted a particular cause outside the realm of his church ministry. Dad just treated people right.

And sometimes, whether they liked it or not, others simply couldn’t help but notice.

***

Go here to download your free Guide, How to Enjoy the Bible Again (when you’re ready) After Spiritual Abuse (without feeling guilty or getting triggered out of your mind). You’ll receive access to both print and audio versions of the Guide (audio read by me). I’m praying it will be helpful.

What a sweet tribute! My favorite: “Treating all people as equals was not an adopted cause but was simply a natural outgrowth of who they were. More like business as usual.”

I’m in tears…what a beautiful and honoring tribute to your Father, your parents….would had loved to know them, yet I will try to do as you wrote about your Father, ” in turbulent times, his influence spread by kindness and consistency.” May God grace us all with that kind of influence…God bless and Happy Fathers Day.

Beautiful! Being a genuine, consistent believer is so “radical” in a fallen world and amidst widespread counterfeit Christianity. What a wonderful heritage he gave his children!

This was beautiful. I too had wonderful parents who in 68 were taking us into Harlem with food, and then we moved to Atlanta from 69-72 and they campaigned for a black candidate (among other things). You can probably imagine the reaction of their friends and neighbors at “these liberal Northerners meddling.” My father once said that he wouldn’t be surprised if we woke up to a burning cross on our front lawn. I am grateful for their legacy and that they gave me a strong sense of justice.

I have a similar story but it happened in the eighties. My dad was a Baptist pastor and a kinder man you couldn’t meet. We had moved to the west coast of Canada. A Chinese Baptist Church was just starting out and their pastor began talking to my dad about renting part of our church building so they could hold services. The racist push back from our congregation was shocking for me to see. I was about 21 and had grown up in the Midwest, going to school through integration in the early seventies. This was different – more covert but racism just the same. I never expected to see it as one always heard how Canada wasn’t like this. My father continued to advocate for this group, it went through and they were able to rent a part of our church. It was a good relationship once some barriers were broken down, but it sure took time.