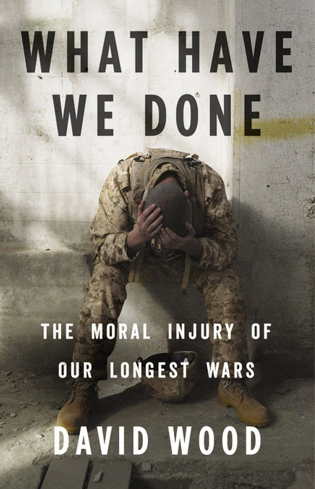

I recently finished reading the book What Have We Done: The Moral Injury of Our Longest Wars, by Pulitzer-prize-winning war journalist David Wood (Little, Brown, 2016). When my husband brought it home from the library my interest was piqued because I hoped it might give me insight into why the abusive situations I’ve known about involved what seemed like a disproportionately high percentage of abusers who were military veterans.

Well, that particular insight didn’t happen. What happened instead was an understanding of the term “moral injury,” which I hadn’t heard before, as well as a growing awareness and understanding of the fact that what David Wood chronicles clinicians as having observed and labelled in ground troops has also appeared in the lives of people I know personally who suffered abuse and betrayal at the hands of people who should have cared for them.

Well, that particular insight didn’t happen. What happened instead was an understanding of the term “moral injury,” which I hadn’t heard before, as well as a growing awareness and understanding of the fact that what David Wood chronicles clinicians as having observed and labelled in ground troops has also appeared in the lives of people I know personally who suffered abuse and betrayal at the hands of people who should have cared for them.

A new descriptive term

Here’s the definition for “moral injury” the doctors arrived at after years of recognizing problems that couldn’t truly be categorized as PTSD:

Here’s the definition for “moral injury” the doctors arrived at after years of recognizing problems that couldn’t truly be categorized as PTSD:

the lasting psychological biological, spiritual, and social impact of perpetuating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations (p 250, boldface mine).

Another term I might use is “inflicted shame.”

David Wood gives war-time examples such as a soldier shooting a child or a soldier watching a buddy get blown up that he thinks he could have or should have saved. Experiences like these don’t simply cause PTSD; in fact, he argues, the effect goes far deeper. To draw the contrast with PTSD, p 18 tells us,

PTSD has little to do with sin. It is a psychological wound caused by something done to you. Someone with PTSD is a victim. A moral injury is a self-accusation, promoted by something you did or something you failed to do, as well as something done to you.

And now I want to repeat that definition, but adding a bit to it in order to apply it to the realm of domestic and sexual abuse:

***

***

Go here to download your free Guide, How to Enjoy the Bible Again (when you’re ready) After Spiritual Abuse (without feeling guilty or getting triggered out of your mind). You’ll receive access to both print and audio versions of the Guide (audio read by me). I’m praying it will be helpful.

Nice article. I just purchased the book!

Thank you, Rebecca! I am trying to explore this important topic with the inmates to whom I minister — one brief mention of it in an article, and a number of them were asking for more information and relating deeply to the concept. If you can suggest any other sources for information about moral injury outside the context of veterans, please do!

I wish I knew of others, but my blog post is the only one I know of right now.

Bessel van der kolk starts off his book “the body keeps score” with that s enario. PTSD used to apply to just men returning from war, but he started to see that other people have PTSD as well.

Yes, that’s the way it was for the psychological community in general. PTSD was applied to soldiers first. Bessel van der Kolk was a leading voice in seeing it applied to others who had experienced trauma. Here’s hoping that Complex PTSD gets in the DSM before long.

This whole concept is so eye-opening to me. I see now that PTSD does not describe the feelings of guilt that many abuse survivors carry. I found a couple of articles that discuss the concept of moral injury in the context of child abuse.

https://richardleemiller.com/blog/faces-of-moral-injury-child-abuse

https://cascw.umn.edu/policy/moral-injury-and-child-welfare/

Thank you for these! They look very helpful.

The term moral injury says to me it was an event a hurtful painful event that happened to the person a derp hurt to their core. It doesn’t label the person who was wronged it labels the act done against them. Freeing them from blame. And as was said they can be healed as it is a derp injury but not a label.

I am so grateful to have stumbled upon your article. I am 66 and since I spoke up about child sexual abuse within my family by someone who was family but also a priest I have lost everything. Family of origin, relatives, old friends and the church who have all refused to acknowledge the reality. My brother is the other witness and he has lost everything too.

I have been treated as having PTSD but your article makes sense of why I don’t feel I am getting”better”. I can finally see the moral injury and huge grief and loss. I hope you write more.

I’m so, so sorry for the terrible things that happened to you. I’ve written quite a lot on bitterness and grief (you can look at those if you search for “bitterness” or if you look at “All blog posts” above), and I recently spoke on Biblical bitterness at a conference, which you can see here: https://heresthejoy.com/2019/04/the-good-news-about-biblical-bitterness-a-short-talk/